About Us Community Forums Documents Homeowners Contact Us ☰

| History | Location | Board Members | Committees |

About Us Community Forums Documents Homeowners Contact Us ☰

| History | Location | Board Members | Committees |

Balmoral is near some of our nation's most historic ground. And our local history is rich with human interest. Here is the story of the surrounding land we now call home.

Balmoral is a community of 179 single family homes, ranging mostly from one to five acres.

As a planned community, we are overseen by the Balmoral Greens Homeowners Association. Located about 25 miles west of Washington, it sits in a beautiful, secluded area of Piedmont hills and woods in southwestern Fairfax County - just over a mile northwest of Clifton proper and about five miles south of Centreville. Almost every modern convenience is no more than twenty minutes away, yet Balmoral is nestled in a discreet 1,150 acre setting near to the historic villages of Union Mills, Clifton, and Centreville. The historic Bull Run and county parkland shape our border to the west and south, while Westfields Golf Course adjoins our northern edge. Wildlife abounds thanks to this open space, while the charming, soft whistle of a distant train can be heard at night just as it was 150 years ago. At least eight street names commemorate early local history or noteworthy 19th-century land owners.

This land assemblage took root in the early 1960s and was complete by late 1980s, but development of Balmoral was delayed due to the economy, zoning reviews, and archeological study. Greenvest L.C. was the developer, acquiring the land through foreclosure in the 1990s.

They introduced three primary builders - NVHomes, Renaissance, and Ryan Homes, plus a few custom builders. Construction began in early 1996, and the first residents moved in during late 1998. Build out was largely complete by 2002, but for a small number of unfinished lots.

The bridge roadway over Johnny Moore Creek opened in 2004, finally allowing for a truly connected community, and the last Fairfax County Performance Bonds were released in 2005. Between 2006 and 2009, the most recent three homes were built. There remains one undeveloped lot on Balmoral Forest Road (in private hands), and two sites on Clifton Quarry and Detwiller Drive are still owned by the developer, as the lots won't perk for county sewer permits.

The first residents in the Balmoral/Clifton area were Stone Age people who arrived at least 11,000 years ago. They could have seen mastodon and bison roam with deer and elk. Man and beast were pushed here from the north by the last Ice Age's advance. Virginia was never under glaciers, which stopped in Pennsylvania, but the prehistoric Balmoral was quite different. The climate was unforgiving, and the Potomac was only a tiny tributary of the lower Susquehanna River (which is now the Chesapeake Bay - at that time the Bay did not exist).

The Ice Age's meltdown yielded more moderate climatic conditions allowing hickory and oak trees to take over rolling grasslands, while an industrious human population expanded.

For centuries prior to the European intrusion, Native Americans peacefully fished, hunted, and grew crops in Northern Virginia. Our predecessors often traveled by foot, establishing common trails that set the path for our modern transportation patterns, as many of today's major roads started as native trails (including Rt. 1 - the main north/south prehistoric trail to our east). They also realized the value of this land's natural stone, using it purposefully. Prehistoric soapstone quarries were mined around Balmoral before 1000 B. C., and at least one important confirmed prehistoric site was within Balmoral. Archaeological discoveries in this area by the Smithsonian in the 1890s became known as the Clifton Quarries. From The Smithsonian's late 19th century research, a fresh picture emerged of the east coast's prehistoric soapstone culture, as our progressive neighbors from the past crafted the soft local soapstone to introduce a variety of new tools, bowls, cooking vessels, and even primitive jewelry.

The Ice Age's meltdown yielded more moderate climatic conditions allowing hickory and oak trees to take over rolling grasslands, while an industrious human population expanded.

For centuries prior to the European intrusion, Native Americans peacefully fished, hunted, and grew crops in Northern Virginia. Our predecessors often traveled by foot, establishing common trails that set the path for our modern transportation patterns, as many of today's major roads started as native trails (including Rt. 1 - the main north/south prehistoric trail to our east). They also realized the value of this land's natural stone, using it purposefully. Prehistoric soapstone quarries were mined around Balmoral before 1000 B. C., and at least one important confirmed prehistoric site was within Balmoral. Archaeological discoveries in this area by the Smithsonian in the 1890s became known as the Clifton Quarries. From The Smithsonian's late 19th century research, a fresh picture emerged of the east coast's prehistoric soapstone culture, as our progressive neighbors from the past crafted the soft local soapstone to introduce a variety of new tools, bowls, cooking vessels, and even primitive jewelry.

European expansionism altered the natives' tranquility. Both French and Spanish explorers were well aware of the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River as early as the 1520s. England's Captain John Smith sailed near the Potomac falls twice during 1608, and Smith also visited the Dogue Indians main village at the mouth of the Occoquan River. The resulting barter by Smith with the natives for harvest saved Jamestown from starvation that winter (it could easily have become just another failed European colony). English Crown interest in our region grew rapidly after John Smith's explorations. In 1649, while living in French exile, English King Charles II granted over 5 million acres north and west of the Rappahannock River - in what was called the Northern Neck Proprietary - to a group of noblemen loyal to the crown. This massive land grant included modern Balmoral and Clifton. It was soon was controlled by Thomas Culpeper, and upon his death it was inherited through his daughter into the Fairfax family. The region remained largely wilderness through the end of the 1600s, but this land grant eventually changed the course of regional history. It was part of the original Stafford County, and later subdivided several times during the 1700s to spawn the original Prince William, Fairfax, and Loudoun counties.

Destiny accelerated in 1719 when a major portion of this Crown grant was inherited by Thomas, sixth Lord of Fairfax. Oxford University educated, Lord Fairfax was thought to be the only British peer ever to move permanently to the colonies, and he became the richest man in Northern Virginia. He gave young George Washington his first job as a junior surveyor at the age of 16. The Virginia House of Burgesses honored the British Peer in 1742 by creating Fairfax County, which then has a population of only 4,000, including about 1,000 slaves. The initial county seat was near modern Tysons Corner, although the seat moved to Alexandria in 1752.

Destiny accelerated in 1719 when a major portion of this Crown grant was inherited by Thomas, sixth Lord of Fairfax. Oxford University educated, Lord Fairfax was thought to be the only British peer ever to move permanently to the colonies, and he became the richest man in Northern Virginia. He gave young George Washington his first job as a junior surveyor at the age of 16. The Virginia House of Burgesses honored the British Peer in 1742 by creating Fairfax County, which then has a population of only 4,000, including about 1,000 slaves. The initial county seat was near modern Tysons Corner, although the seat moved to Alexandria in 1752.

Documented history near modern Balmoral begins in the early 1700s. This area was the backcountry to the merchants of Alexandria and Georgetown; agriculture dominated, with tobacco being the focal crop until it burned out our rocky soil. Several Indian trails nearby were expanded into rolling roads so that tobacco hogsheads could be rolled down to the river ports; modern Braddock Road was called Walter Griffin's Rowling Road.

The winding Colchester Road - northeast of modern Clifton - was a thoroughfare to the once bustling but now extinct port of Colchester, near the juncture of the Occoquan and Potomac Rivers. A 1748 map of the region showed Bull Run, while a 1760 map showed Turley's Mill on the north side of Popes Head Creek. At least 5 members of the extended Turley family owned land nearby, while much of western Balmoral appears to have been owned by James and Tyler Waugh, and possibly Peter Carter, Thomas Church and the Linton heirs. From 1757 until 1798, the western Fairfax/Loudoun County border started very nearby at the intersection of Popes Head Creek and Bull Run.

North of Balmoral, a crossroads village emerged by the mid 1700s known as Newgate, which is now called Centreville. A stone boundary marker was found in modern Centreville with a 1739 date. Lane's Store was soon established as a place to sell dry goods, slaves, and land, then Newgate Tavern opened, and by the early 1770s, Newgate had become the village name. The third structure built in Newgate was Mount Gilead - an historic site today and the only surviving building from Newgate. In 1792, the Virginia Assembly renamed it, chartering a town called Centreville. One legend claims that the name was derived because it was almost equidistant from the region's six dominant towns at the time - Alexandria, Washington, Georgetown, Leesburg, Middleburg and Warrenton.

North of Balmoral, a crossroads village emerged by the mid 1700s known as Newgate, which is now called Centreville. A stone boundary marker was found in modern Centreville with a 1739 date. Lane's Store was soon established as a place to sell dry goods, slaves, and land, then Newgate Tavern opened, and by the early 1770s, Newgate had become the village name. The third structure built in Newgate was Mount Gilead - an historic site today and the only surviving building from Newgate. In 1792, the Virginia Assembly renamed it, chartering a town called Centreville. One legend claims that the name was derived because it was almost equidistant from the region's six dominant towns at the time - Alexandria, Washington, Georgetown, Leesburg, Middleburg and Warrenton.

Centreville grew in the early 1800s as a modest trading center, with nearby business including tanneries, grist and lumber mills. But road, rail and war eventually subordinated Centreville's standing. The Little River Turnpike, finished in 1806, diverted economic growth to the north (today known only as Rt. 236, in those days this toll road extended from Alexandria to Fairfax City then along modern Rt. 50 past Chantilly out to the Blue Ridge Mountains). The Warrenton Turnpike (modern Rt. 29) helped boost Centreville upon its 1828 completion.

However, the 1851 opening of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad bypassed Centreville to the south, as did the Manassas Gap Railroad to the west. In 1854, a rail interchange was built for these two lines at a hamlet west of modern Balmoral called Tudor Hall (honoring a nearby plantation). Tudor Hall was quickly renamed Manassas Junction, and then later shortened to Manassas; this new rail town rapidly eclipsed Centreville. Railroad growth would continue to have a profound impact on our Northern Virginia Piedmont region for decades to come. Farmers finally gained access to major markets without the need for ports. Even today, these two original rail lines are still an active part of the Norfolk Southern system. The merged rail line crosses the Bull Run over a bridge just through the woods below Balmoral at the southern end of Detwiller Drive, and this bridge would soon assume historic importance.

However, the 1851 opening of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad bypassed Centreville to the south, as did the Manassas Gap Railroad to the west. In 1854, a rail interchange was built for these two lines at a hamlet west of modern Balmoral called Tudor Hall (honoring a nearby plantation). Tudor Hall was quickly renamed Manassas Junction, and then later shortened to Manassas; this new rail town rapidly eclipsed Centreville. Railroad growth would continue to have a profound impact on our Northern Virginia Piedmont region for decades to come. Farmers finally gained access to major markets without the need for ports. Even today, these two original rail lines are still an active part of the Norfolk Southern system. The merged rail line crosses the Bull Run over a bridge just through the woods below Balmoral at the southern end of Detwiller Drive, and this bridge would soon assume historic importance.

While Centreville struggled to gain the standing that its name suggests, its location helped set the stage for Union Mills, and then eventually Clifton and Balmoral.

South of Centreville, the rocky landscape was mostly unsuitable for crop farming. By the late 1700s, grazing for sheep and dairy replaced cash crops like tobacco and wheat (and grazing prevailed here well into the 1900s). But this rocky, sloping topography lent itself well for mills, with many water runoffs feeding Bull Run and the Occoquan River. Milling was an essential part of colonial and early America. Grinding grain was critical to making bread and livestock feed, and the local government actively encouraged landowners to construct mills - George Washington's Grist Mill at Mount Vernon was one of the region's largest and most productive. By the early 1800s, several mills appeared around southwestern Fairfax, including ones operated by the Turleys, Kinchloes, and Pollards on Popes Head Creek, with others on Johnny Moore Creek and Bull Run.

In 1809, John Dixon Dye received a permit to build a new mill operation on the south bank of Popes Head Creek at its juncture with Bull Run. He built three mills and a milldam, naming the operation Union Mills, and gradually that name was adopted for the larger region - including Balmoral. The actual Union Mills site was just south of Balmoral's edge - through the woods south of Quigg Street and Balmoral Forest, and then across the Popes Head - in the northwest corner of modern Hemlock Overlook Regional Park.

In 1809, John Dixon Dye received a permit to build a new mill operation on the south bank of Popes Head Creek at its juncture with Bull Run. He built three mills and a milldam, naming the operation Union Mills, and gradually that name was adopted for the larger region - including Balmoral. The actual Union Mills site was just south of Balmoral's edge - through the woods south of Quigg Street and Balmoral Forest, and then across the Popes Head - in the northwest corner of modern Hemlock Overlook Regional Park.

Also known as Popeshead Mill and Dye's Mill, it became a substantial business. The Dye family lived in a house just upstream from the miller's house, while more families were attracted to the area and sought to buy the meaningful land holdings north and south of Popes Head Creek. With the Dyes and other locals like the Beckwiths and Kinchloes (whose namesakes still live southeast of Clifton), new names would appear including Hooe, Cannon, Detwiller, and Buckley. The dirt wagon track leading north toward Centreville became named Union Mill Road, and there was a documented tavern along that road owned by William Willcoxon (a different Willcoxon started a famous tavern in Fairfax City that lasted for 90 years). Mr. Willcoxen later bought the main Union Mills after Mr. Dye's death. A small cemetery was documented by the County behind Balmoral Forest Road where Widow Mary Willcoxon's house once was. Even today, ruins and remnants of mill related structures can be found throughout the woods around Balmoral.

The Union Mills area became so active that in the early 1850s a train station was built for the Orange and Alexandria Railroad on the mill creek's north bank, and a U.S. post office opened there in 1855. However, it had to be named Dye's Mill Post Office, for another town near Charlottesville in Fluvanna County, Virginia was already called Union Mills. The little village grew but Union Mills never had a documented store (the closest known store was in Centreville), nor a church. While not an official town, the future of Union Mills clearly had promise as the curtain of conflict and strife came down in 1861.

At the start of the Civil War, western Fairfax County was hotly contested geography and became military territory - occupied throughout the war first by the Confederacy and then the Union. In the Union Mills area, 276 men were eligible to vote on the secession question. Of the 105 who went to the Centreville polling place in May 1861 to vote on the secession question, all voted in favor. As with much of Virginia, the driving political issue was not slavery, but a refusal to take up arms against the other southern states that had already seceded.

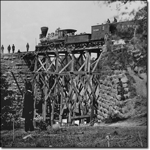

Union Mills' location proved costly, particularly because our railroad became critical to national interests. Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee both took trains through the rail lines that pass nearby. The Bull Run rail bridge at Union Mills was a important target, destroyed and rebuilt seven times from 1861-64. War anxiety would have consumed local residents, and many left the area for the duration of the conflict, for the War almost obliterated the surrounding locale. Until the spring of 1862, Union Mills Road was literally part of the northern borderline of the Confederacy, as the roads from Leesburg to Centreville then southeast to Dumfries were the northernmost perimeter of Confederate control outside the edge of the defense of Washington.

Union Mills' location proved costly, particularly because our railroad became critical to national interests. Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee both took trains through the rail lines that pass nearby. The Bull Run rail bridge at Union Mills was a important target, destroyed and rebuilt seven times from 1861-64. War anxiety would have consumed local residents, and many left the area for the duration of the conflict, for the War almost obliterated the surrounding locale. Until the spring of 1862, Union Mills Road was literally part of the northern borderline of the Confederacy, as the roads from Leesburg to Centreville then southeast to Dumfries were the northernmost perimeter of Confederate control outside the edge of the defense of Washington.

Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston used Mount Gilead in Centreville as his headquarters during the winter of 1861-62. Two forts were constructed by the Confederates where Balmoral Greens Avenue is today, and that land is now a protected historic area for Fairfax County. At least one of those forts (probably the one opposite where Cannon Fort Drive intersects with Balmoral Greens) was called Camp Early - also nicknamed Measles Camp. A third fortification is known to have been south of Cannon Fort Drive overlooking Bull Run at McLean's Ford. In March 1862, the Confederate Army abandoned this area to pull out of Northern Virginia and set a better defense line for Richmond stretching from Fredericksburg west to the mountains. The Union Army assumed many of the abandoned positions, including the forts nearby.

The First and Second Manassas battles were fought to control the railroads. Much of the local land was stripped bare of trees, which were used for firewood or to build troop encampments. As a result, battles and skirmishes could have been heard easily and possibly seen from some present home sites. War noise would have been deafening - on August 27, 1862 (the day before the start of Second Manassas), Gen. Stonewall Jackson personally ordered the Bull Run train bridge at Union Mills to be blown up. That same day a skirmish occurred around the southern edge of Balmoral, below Detwiller Drive and Weymouth Hill Road near where Johnny Moore Creek enters Bull Run - just north of the bridge.

After Second Manassas, Centreville was overrun and torn apart by retreating troops and military movement, and afterwards it was essentially abandoned. This remained Union controlled land for the balance of the war, and Northern Virginia was once again under one flag - the American stars and stripes.

After Second Manassas, Centreville was overrun and torn apart by retreating troops and military movement, and afterwards it was essentially abandoned. This remained Union controlled land for the balance of the war, and Northern Virginia was once again under one flag - the American stars and stripes.

With the Confederate pullback, the local Union military focused on maintaining the railroads, which were critical to the movement of federal troops and supplies to western and southern Virginia. Manassas became a massive supply depot and transportation hub. The Union Mills train station was very important due to its proximity to the bridge crossing Bull Run, and that rail bridge became one of the nation's most famous and most photographed during the War. A skirmish occurred on October 16, 1863 north of the bridge, just above the McLean Ford's fortifications. Due to constant guerrilla raids on the railroad, the federal government ultimately ordered all remaining residents who lived near the tracks to leave the region. Activity grew such that another train depot was deemed necessary. In 1863, the U.S. Army commissioned new construction one mile east of the Union Mills Station - a railroad siding used for supply storage that was named Devereaux Station.

One noteworthy threat to the nearby Union lines was a single man - and his loyal band of partisan militia. John Singleton Mosby - former UVA student, lawyer, Confederate officer, future U.S. ambassador - ran guerrilla raids behind enemy lines in Northern Virginia for most of the War's final two years, extending the hostilities by several months. Only Revolutionary War hero Francis Marion may have been a better guerrilla tactician. This area was near the edge of Mosby's Confederacy. Col. Mosby was in or near this area many times, often disrupting rail operations, and it was well documented that Mosby's Rangers enlisted several Union Mills residents, including members of the Kinchloe family.

With the Civil War's end, shattered residents around Union Mills returned to their land and took the oath of allegiance to the Union. Their homes were not the same - lives were lost, farms had been dug up and carved up, houses were ransacked, torched, or destroyed. But those who did return started to move on with their lives. Dye's Mill U.S. Post Office at Union Mills reopened in the fall of 1865 with a new postmaster, John L. Detwiller, whose family had purchased 160 acres of Union Mills land (now Balmoral) in 1860. Newcomers were drawn to the region as well, and those newcomers brought money and new energy for change. Three important transitions would fuel rapid change for the Union Mills area.

First, land ownership shifted for the first time in decades, as several large farms changed hands, with the most important change occurring due to William E. Beckwith's death in 1863. He willed large parcels to both his estate for the benefit of his family and to his freed slaves. The slaves got over 200 acres along the valley just south of Popes Head Creek (which is now much of downtown Clifton). And when his estate settled in 1866, over 1,000 acres north of the creek was sold off (again part of Clifton proper including the Clifton Elementary School site). Also, the Detwiller family expanded their holdings significantly and would own some of that land for almost 100 more years, even opening a new mill on Johnny Moore Creek. In addition, the Quigg family bought and sold land around the area that would impact future land assemblages.

Second, the railroads helped revitalize this entire region. In particular, the new rail depot one mile east of Union Mills was expanded, and it proved pivotal to post-war economic development. Named Devereaux Station to honor of its engineer builder, its name was changed in 1868 to Clifton Station, and a village emerged around the new train station that became known as Clifton Station also. This remained its name until 1902, when the Virginia General Assembly approved the incorporation for the town of Clifton. Interestingly, during the wartime construction of the rail siding, this area was still called Union Mills. Therefore, neither Clifton nor Clifton Station had any antebellum roots. Much of that land around the new rail siding had been owned by William Beckwith, and there were some buildings scattered nearby, including a house that still exists in Clifton (the Beckwith House) which dates to the 1770s. As such, Clifton is purely a post-Civil War village.

Second, the railroads helped revitalize this entire region. In particular, the new rail depot one mile east of Union Mills was expanded, and it proved pivotal to post-war economic development. Named Devereaux Station to honor of its engineer builder, its name was changed in 1868 to Clifton Station, and a village emerged around the new train station that became known as Clifton Station also. This remained its name until 1902, when the Virginia General Assembly approved the incorporation for the town of Clifton. Interestingly, during the wartime construction of the rail siding, this area was still called Union Mills. Therefore, neither Clifton nor Clifton Station had any antebellum roots. Much of that land around the new rail siding had been owned by William Beckwith, and there were some buildings scattered nearby, including a house that still exists in Clifton (the Beckwith House) which dates to the 1770s. As such, Clifton is purely a post-Civil War village.

The third major change would leverage the first two noted above, and drive rapid growth for Clifton Station. A northern newcomer from New York named Harrison Otis saw the opportunity for new development. He essentially founded Clifton Station, rapidly acquiring local land, amassing over 1,000 acres by early 1868 (including a large piece of the Beckwith estate). He planted vineyards on the hill where Clifton Elementary School now sits, and he built a hotel near the new train station - now the Trummer's on Main restaurant. The economic energy and focus quickly pulled away from Union Mills. By 1868, the train pulled away too, as Union Mills Station was closed. And in 1869, Harrison Otis got the post office transferred to Clifton Station, and he was named its first postmaster. The new town was now on the map.

Clifton Station prospered well into the 1900s, and the new town soon had four stores and strong commercial activity. Union Mills did not die immediately. The area retained the name for many years, and people continued to live near the defunct mill. But the shift toward Clifton Station was unstoppable. Other regional change also accelerated. The Detwiller family mill on Johnny Moore Creek had such an impact that by the late 1880s, Union Mills Road was unofficially referred to as Detwiller's Road. With replanting, the lumber industry sprouted throughout the region, and gradually replaced agriculture as the primary business. Also, stone quarrying made a post Civil War resurgence. It became an important industry, ahead of the Smithsonian's archeological research revealing that this was the merely the second coming of the local quarry business.

Clifton Station became listed in guidebooks as a resort by the late 1800s. The main hotel built by Otis - then called the Clifton Hotel (later know as the Hermitage Inn, and now Trummer's on Main) became a popular destination. Legend has it that Presidents Grant, Hayes and Garfield and Teddy Roosevelt visited. Also, President Grant and John Singleton Mosby had become good friends, and legend has it that they met at the Clifton Hotel in the winter of 1877. Soon thereafter, Grant supposedly suggested that his successor, President Hayes, choose Mosby as U.S. Consul to Hong Kong (he served from 1878-1885). By the end of the 19th century, Clifton Station had grown to be the biggest town in Fairfax County, which justified its charter as the town of Clifton, as approved by the Virginia General Assembly on March 10, 1902.

Clifton Station became listed in guidebooks as a resort by the late 1800s. The main hotel built by Otis - then called the Clifton Hotel (later know as the Hermitage Inn, and now Trummer's on Main) became a popular destination. Legend has it that Presidents Grant, Hayes and Garfield and Teddy Roosevelt visited. Also, President Grant and John Singleton Mosby had become good friends, and legend has it that they met at the Clifton Hotel in the winter of 1877. Soon thereafter, Grant supposedly suggested that his successor, President Hayes, choose Mosby as U.S. Consul to Hong Kong (he served from 1878-1885). By the end of the 19th century, Clifton Station had grown to be the biggest town in Fairfax County, which justified its charter as the town of Clifton, as approved by the Virginia General Assembly on March 10, 1902.

Land transfers not only set the stage for growth, but would also lead to one of the area's most compelling human stories - the creation of Ivakota Farm, which was largely on ground now part of Balmoral.

The story began in 1900 when James Bradley bought the Fletcher family's dairy farm for $5,000 (land which the Fletchers had purchased in the 1880s from the Quigg family). A Massachusetts transplant, Bradley continued the existing dairy operation but also quickly became active in timber, sawmilling, and quarrying. His aggressive push to dominate the local quarry trade caused him to become overextended financially, and he lost the main farm in 1905 to foreclosure by the National Bank of Manassas.

Frank and Ella Shaw bought those 264 acres from the Manassas bank in 1907 for $7,000. They renamed it Ivakota in honor of the three states Mrs. Shaw had lived in - Iowa, Virginia and North Dakota. Mrs. Shaw was very interested in the emerging anti-vice movements nationally. But when her husband died in 1913, her interest in maintaining the farm waned while her social conscience grew. On May 3, 1915, Mrs. Shaw conveyed the farm as a donation to the National Florence Crittenton Mission (NFCM) of Alexandria. This was run by an Alexandrian, Dr. Kate Waller Barrett, a medical doctor and Episcopal minister's widow who had become a prominent Progressive Era figure and national anti-vice movement leader. She wanted to create the house of another chance with a countryside home for girls and young women of ill repute - young people on whom society would otherwise give up, but where they could benefit from the right sort of living.

Frank and Ella Shaw bought those 264 acres from the Manassas bank in 1907 for $7,000. They renamed it Ivakota in honor of the three states Mrs. Shaw had lived in - Iowa, Virginia and North Dakota. Mrs. Shaw was very interested in the emerging anti-vice movements nationally. But when her husband died in 1913, her interest in maintaining the farm waned while her social conscience grew. On May 3, 1915, Mrs. Shaw conveyed the farm as a donation to the National Florence Crittenton Mission (NFCM) of Alexandria. This was run by an Alexandrian, Dr. Kate Waller Barrett, a medical doctor and Episcopal minister's widow who had become a prominent Progressive Era figure and national anti-vice movement leader. She wanted to create the house of another chance with a countryside home for girls and young women of ill repute - young people on whom society would otherwise give up, but where they could benefit from the right sort of living.

Kate Waller Barrett was an extraordinary person. She was a delegate to the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference that ended WWI, and she was President of the NFCM. Barrett helped found the Virginia State Chapter of the D.A.R. She gave a vice-presidential nominating speech as a Virginia delegate to the 1924 Democratic National Convention. Upon her sudden 1925 death, Dr. Barrett was the first woman in Virginia history to have the flag over the Richmond Capitol lowered to half-mast. Today, the Alexandria City Library Building in Old Town, a dormitory at the College of William & Mary, and two elementary schools in Arlington and Stafford Counties respectively are named in her honor.

Dr. Barrett transformed Ivakota Farm into a progressive reform school and home for unwed mothers and their children. The farm grew into a campus including residence halls for disadvantaged young women, a nursery, health clinic, vegetable canning operation and an award winning industrial farm training center (which received county, state and federal funding). Over a dozen buildings and cottages were constructed, all supporting the lives of delinquent, often incorrigible and venereally diseased young women, many of whom were assigned legal detention there by the juvenile courts. But unlike so many other homes, Ivakota had a focus of hope and rehabilitation, with medical and moral treatment aimed at establishing proper values and returning healthy young women to the city with a socially, morally and economically fit perspective.

It was home through the years to an estimated 1,100 women, and at its peak, the out-patient health clinic treated over 9,000 women a year. While Ivakota Farm lost momentum after 1940, some of its programs operated until 1958, and it allowed other charities to use the grounds for programming as well in later years. However, NFCM sold the farm in 1962. The ruins of its main hall were last photographed in 1988. Its cemetery was incorporated into the Balmoral community's common area, and it remains the last physical evidence of this unique legacy.

To commemorate the remarkable Ivakota Farm story, the Fairfax County History Commission approved an historic marker for placement in Balmoral. It was dedicated on Mother's Day weekend in May of 2007.

To commemorate the remarkable Ivakota Farm story, the Fairfax County History Commission approved an historic marker for placement in Balmoral. It was dedicated on Mother's Day weekend in May of 2007.

The 20th Century produced progress coupled with serenity. Initially, much of the Union Mill and Clifton area remained farmland, with dairy and grazing land predominating, and the mills were largely closed by the early 1900s. The timber industry wore itself out with over-foresting, which finally allowed pines and hardwoods gradually to take permanent root. As a result, today, few trees locally are more than 75 years old. The quarry and stone business continued with some success. It goes on, as evidenced by the massive Luck Stone Quarry just west of Centreville on Rt. 29.

An electric power company was formed on Bull Run in the 1920s and provided power and jobs in the area until the Second World War. This company was ultimately merged into what is now NOVEC, which supplies power to the Balmoral area. Population in Fairfax County leaped forward as the military-industrial complex grew to support WW II, and growth exploded after the war. From 1946-60, Fairfax was the nation's fastest growing county. Farmland in Arlington, McLean, and Vienna disappeared as homes and buildings rose. Over 16,000 acres was dedicated to create Dulles International Airport, which opened in 1962. Planning for what would become the Fairfax County Parkway began in the 1950s when a second and third Beltway around Washington was being debated. The second and third Beltways were never built, but the first section of the Fairfax County Parkway opened in April 1987.

Despite what was going on nearby, the Union Mills and Clifton region retained much of its nestled feel even as other parts of Fairfax County were densely developed. Contrary to most of Fairfax, growth in this region slowed for several decades. Passenger rail service in Clifton ceased in 1938 due to lack of demand, while freight service was discontinued in 1958. Most of the older families of Union Mills sold off their land, including the Detwillers. Other large farms were gradually broken up, although to this day Clifton has a relatively large amount of five or more acre parcels. This region sustains the last small vestiges of Fairfax County horse country. Local residents fought growth, successfully blocking on several occasions ideas for new major roads being introduced in or around Clifton. Fairfax County leaders moved in 1959 to preserve some open land by founding the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority (NVRPA). Balmoral's southern and western edges adjoin county parkland because of this, as part of a ribbon of greenway and park stretching continuously from Bull Run battlefield almost to Mason Neck and Mount Vernon. In 1962, a 225 acre parcel was acquired by the NVRPA, and became Hemlock Overlook Regional Park. It included the site of the original Union Mills. Also historic preservation in Clifton has permitted much of its Victorian charm to be preserved and restored.

Despite what was going on nearby, the Union Mills and Clifton region retained much of its nestled feel even as other parts of Fairfax County were densely developed. Contrary to most of Fairfax, growth in this region slowed for several decades. Passenger rail service in Clifton ceased in 1938 due to lack of demand, while freight service was discontinued in 1958. Most of the older families of Union Mills sold off their land, including the Detwillers. Other large farms were gradually broken up, although to this day Clifton has a relatively large amount of five or more acre parcels. This region sustains the last small vestiges of Fairfax County horse country. Local residents fought growth, successfully blocking on several occasions ideas for new major roads being introduced in or around Clifton. Fairfax County leaders moved in 1959 to preserve some open land by founding the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority (NVRPA). Balmoral's southern and western edges adjoin county parkland because of this, as part of a ribbon of greenway and park stretching continuously from Bull Run battlefield almost to Mason Neck and Mount Vernon. In 1962, a 225 acre parcel was acquired by the NVRPA, and became Hemlock Overlook Regional Park. It included the site of the original Union Mills. Also historic preservation in Clifton has permitted much of its Victorian charm to be preserved and restored.

As for Balmoral, a series of land assemblages beginning in the 1960s gradually set the stage for our community's existence. An investment group of three men bought over 300 acres in the area in about 1965 and retained it for more than 20 years until it was acquired for incorporation in the late 1980s Balmoral assemblage. The Ivakota grounds went into investor hands in 1979, and then became part of the Balmoral assemblage in 1987.

Meanwhile, other nearby areas started to mushroom with growth, particularly as I-66 opened in 1980 and Metro went to Vienna soon thereafter. For example, just north of Balmoral became the location for Little Rocky Run - with almost 1,000 acres, this huge planned community financed by Riggs National Bank opened in 1983 and now supports more than 2,700 homes and nearly 10,000 residents. The future Balmoral community emerged more slowly due to planning delays and the early 1990s economic recession.

The Clifton General Store once had a hand-drawn map of a pro-forma Balmoral that hung for many years near the ice cream box and ATM. Of unknown date, the store's owners say it was drawn in the late 1980s by a store employee. It showed a hypothetical community that never got planning permission - Balmoral Greens Avenue was to be called Champions Way, which would have been the address for the Westfields Golf Club. While some planned streets look very similar today, others differ greatly. That exact plan was not approved, but the golf club did come into being as a Fred Couples design for a semi-private course. The golf club opened on Balmoral Greens Avenue in 1998, and its clubhouse has since been the setting for many HOA social functions. As they say, the rest is history.

Balmoral is a thoroughly modern community featuring a diverse mix of residents. Residents include government employees, as well as executives from the worlds of defense contracting, telecommunications, technology, finance, construction and services, along with doctors, specialty consultants, senior international agency staff, lawyers, active duty and retired senior military officers, and owners of privately-held businesses. Some moved here from homes very nearby in, Little Rocky Run, Centreville, or Fairfax, while others arrived here from across the nation and the world. It is not just a faceless bedroom community, but rather it is a family oriented and socially active neighborhood. Noteworthy community events quickly became tradition. The neighborhood has an annual autumn picnic and Halloween Parade, a wine club, a book club, ladies bunko groups, a tennis group, and plenty of golf foursomes. The Progressive Dinner has drawn great interest as residents venture from home to home trying different tastes from each host cook's specialty. It is a kids friendly place, where crime has been minimal and there is a true sense of caring among residents. People get to know their neighbors, so one can have privacy while still having others to reach out to.

Balmoral is a thoroughly modern community featuring a diverse mix of residents. Residents include government employees, as well as executives from the worlds of defense contracting, telecommunications, technology, finance, construction and services, along with doctors, specialty consultants, senior international agency staff, lawyers, active duty and retired senior military officers, and owners of privately-held businesses. Some moved here from homes very nearby in, Little Rocky Run, Centreville, or Fairfax, while others arrived here from across the nation and the world. It is not just a faceless bedroom community, but rather it is a family oriented and socially active neighborhood. Noteworthy community events quickly became tradition. The neighborhood has an annual autumn picnic and Halloween Parade, a wine club, a book club, ladies bunko groups, a tennis group, and plenty of golf foursomes. The Progressive Dinner has drawn great interest as residents venture from home to home trying different tastes from each host cook's specialty. It is a kids friendly place, where crime has been minimal and there is a true sense of caring among residents. People get to know their neighbors, so one can have privacy while still having others to reach out to.

The last 200 years have woven a tapestry of local color around the area known as Union Mills, Clifton, and Balmoral. Clifton was once the biggest town in Fairfax and now it is the smallest. Families named Detwiller, Beckwith, and Quigg changed the region that we now call home - and we have streets named for each of them. We all enjoy the common bond that our homes rest near ground forever linked to the establishment of America. And yet Balmoral contains its own rich history, which is being added to every day. If allowed, our history easily forgotten or rendered trivial in the haste of modern life and the pace of transformation that Northern Virginia has endured. But if preserved, our history is a source of great human interest that deserves celebration. And it sets the stage for the dreams of our future.

Balmoral - some might think it odd or silly that there is a reference to Scotland in southwestern Fairfax County. Is it simply a well-chosen marketing name, or is it because the landscape resembles the rocky Scottish Highlands where the British Royal family has a home? Many residents may not appreciate the Scottish influence all around our nation's capital. The Census Bureau says the Greater DC Area has 1,979 official place names. Over 17% of these are based in whole or part on actual Scottish place names, family names or derivative words. As such, experts think that the Washington, DC region may have the highest urban concentration of Scottish related place names in all of America! Regional examples include Annandale, Ashburn, Avenel, Largo, Logan Circle, McLean, Rosslyn, Sterling and Tantallon. Closer to home, places like Alexandria, Clifton, Dale City, Dumfries, Springfield and Wellington all have Scottish root. So, perhaps the Scottish inference is not really out of place.

Balmoral - some might think it odd or silly that there is a reference to Scotland in southwestern Fairfax County. Is it simply a well-chosen marketing name, or is it because the landscape resembles the rocky Scottish Highlands where the British Royal family has a home? Many residents may not appreciate the Scottish influence all around our nation's capital. The Census Bureau says the Greater DC Area has 1,979 official place names. Over 17% of these are based in whole or part on actual Scottish place names, family names or derivative words. As such, experts think that the Washington, DC region may have the highest urban concentration of Scottish related place names in all of America! Regional examples include Annandale, Ashburn, Avenel, Largo, Logan Circle, McLean, Rosslyn, Sterling and Tantallon. Closer to home, places like Alexandria, Clifton, Dale City, Dumfries, Springfield and Wellington all have Scottish root. So, perhaps the Scottish inference is not really out of place.

This information has been compiled from extensive personal study, reading, and touring of Northern Virginia over four decades. Little or none of the information contained above is original, and almost all of this information is in the public domain. Certain primary sources were relied upon extensively, while other sources were largely of a secondary or tertiary nature.

Research has been conducted at museums and centers including Mount Vernon, Gunston Hall, Manassas Battlefield National Park, Sully Plantation, Fairfax City, and Manassas City as well as the Fairfax County Circuit Court Archives, Alexandria City Library, the Virginia Room of the Fairfax County Library, College of William & Mary Archives, and the web site for Fairfax County.

Books providing major reference material include Clifton: Brigadoon in Virginia by Nan Netherton, Stone Ground - A History of Union Mills by Paula Elsey, Fairfax County and the War Between The States by the Fairfax County Park Authority, A History of Fairfax County by the 1951 Fairfax County Historical Society (including A History of Clifton by Richard Randolph Buckley), George Washington's Grist Mill at Mount Vernon by Dr. Dennis Pogue and Dr. Esther White, Mosby's Rangers by Virgil Carrington Jones, and articles from Civil War Times Illustrated, Northern Virginia Heritage, and Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine.

This paper is not intended to be an original work or professional treatise, but has been assembled as an educational piece for the good of the Balmoral community, and as a means to preserve local legacy for those interested in Balmoral and its environs. Any errors or mistakes in content are those solely of the editor. Northern Virginia is blessed with national treasures such as Mount Vernon, Gunston Hall, and Sully Plantation, as well as historic and beautiful open spaces and landscapes such as the Manassas National Battlefield, the Bull Run-Occoquan Regional Park, and Green Springs. Among other advocates, the Fairfax County History Commission promotes the preservation of our regional heritage, as have many superior writers over the past 200 years.

Andy Morse, Editor